At its core, the Crisis Communication in Niagara project is a research endeavor — we are attempting to analyze a segment of the web and derive meaning out of thousands of websites, text documents, images, and other file types. Many of us are also teachers; naturally, we have an interest in the pedagogical implications of presenting the web as a source of data.

How do we best introduce students with little or no background to this topic? To scratch this pedagogical itch, members of the team (Tim Ribaric, Cal Murgu, Karen Louise-Smith) developed a course module that reframes the web as a rich data source, rather than simply a medium to browse, explore, and consume. The a/synchronous module was featured in Dr. Karen Louise-Smith’s 4th Data and Society course. The learning objectives of the module were as follows:

- O1: Introduce students to the technical and ethical aspects of web archiving

- O2: Offer opportunities for students to experience web archives as users and as technicians

To meet these objectives, we created the module using a ‘flipped-classroom’ model: students completed an asynchronous lecture and a series of DIY activities in the LMS, followed by a synchronous ‘sensemaking’ session on October 20th.

Ahead of the ‘sensemaking’ session on October 20th, students were asked to read the following articles:

McCrow-Young, A. (2021). Approaching Instagram Data: Reflections on Accessing, Archiving, and Anonymising Visual Social Media. Communication Research and Practice, 7(1), 21-34.

Lin, J., Milligan, I., Oard, D. W., Ruest, N., and Shilton, K. (2020). We could, but should we? Ethical considerations for providing access to GeoCities and Other Historical Digital Collections. CHIIR ‘20: Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Human Information Interaction and Retrieval , 135-144.

The recorded lecture (embedded below) covers the basics of web archives, including what they are, how they function, and why we should be interested in preserving the web. The lecture is bookended by the #freedaleaskey story, expertly described by Ian Milligan, Nick Ruest, and Anna St. Onge in their article in Digital Studies.

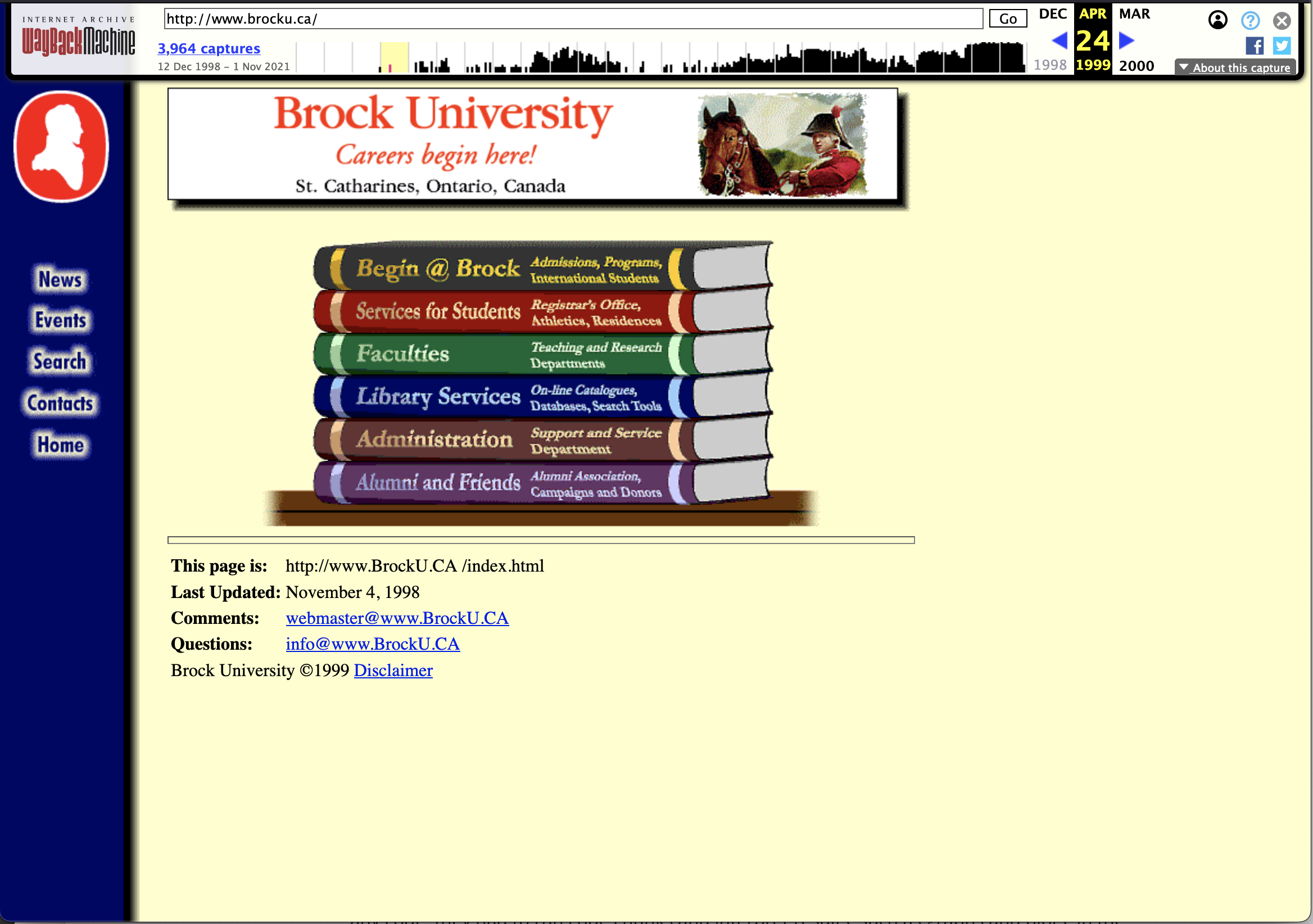

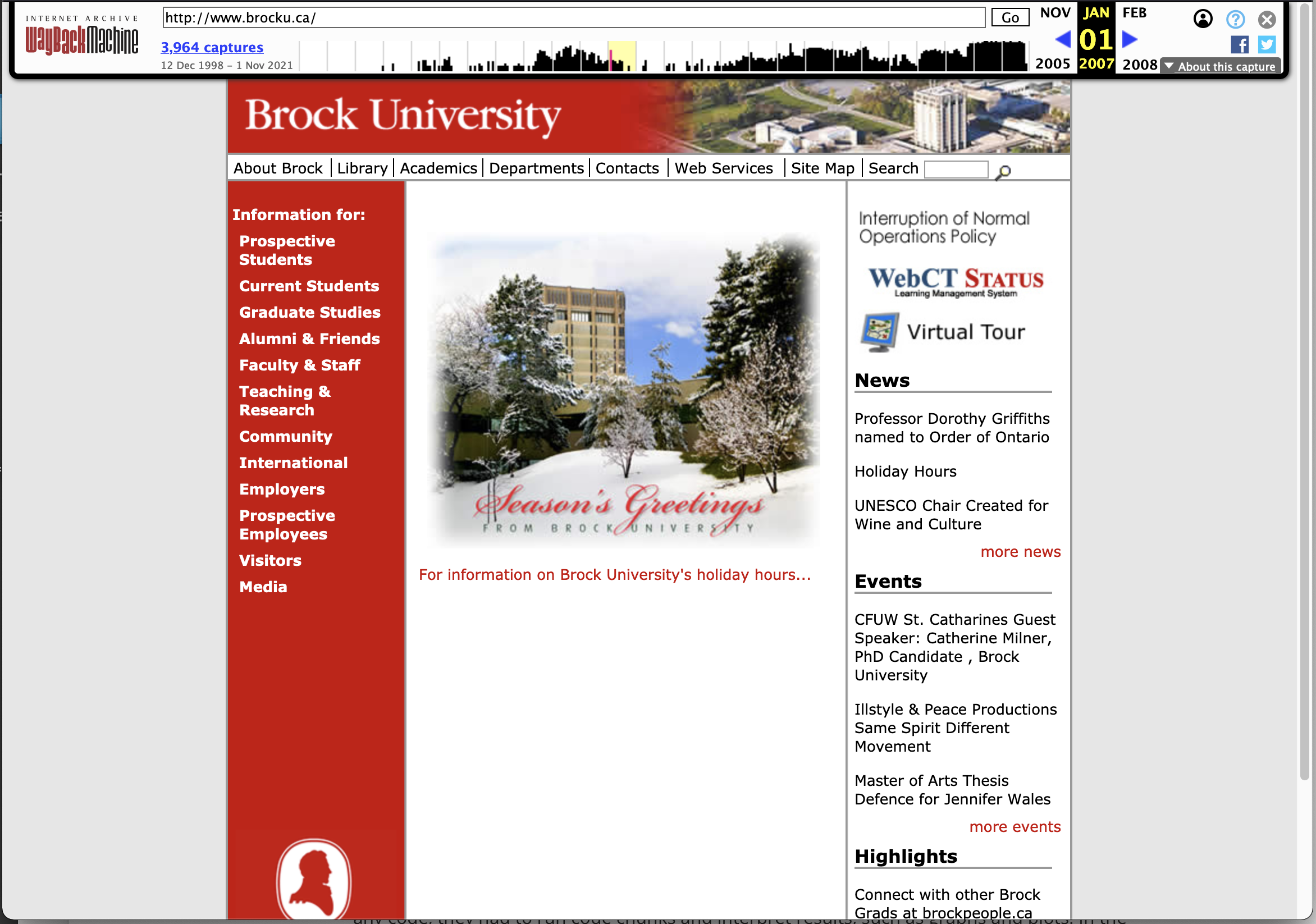

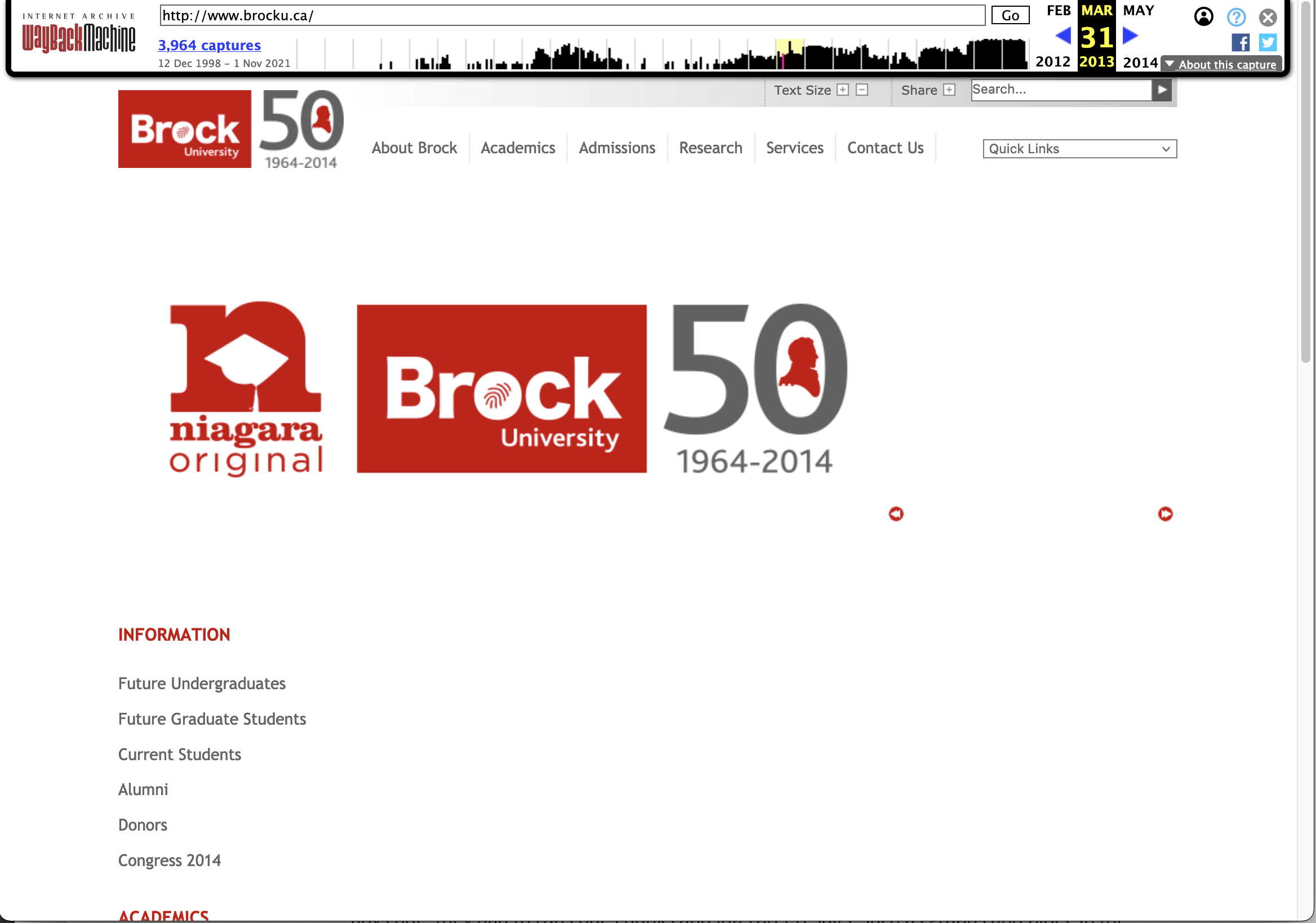

Following the lecture, students were asked to complete a series of activities to meet the second objective. The first activity invited students to visit the WayBack machine and search for a website that is important to them. To visualize change over time, students had to explore three different snapshots of the same url and describe the changes that they observed in several sentences. As an example, snapshots of the Brock University website from 1999, 2007, and 2013 were shown.

Circa 1997

Circa 1997

Circa 2007

Circa 2007

Circa 2013

Circa 2013

Student responses gestured to the interesting information that we can derive from an analysis of how websites can change over time. For instance, a researcher may focus on branding and promotion efforts, or how product launches have changed in relation to the growth of the company.

The second activity asked students to assume the role of an analyst by exploring a computational notebook. The computational notebook was created in Google Colab by Tim Ribaric. The notebook features a variety of scripts that analyze crawl rates, top urls by crawl frequency, change of text on a page over time, and sentiment analysis using TextBlob. While students did not have to write any code, they had to run code chunks and interpret results, such as graphs and plots. In the concluding section of the notebook, students were asked to change a variable (the url of a page), and reflect on the subsequent analysis. Without question, this activity represented the most challenging task in this module.

The final activity required that students synthesize the entire lesson into a thoughtful response to the following question:

Suppose that you’ve been asked to create a policy for web archiving Brock University’s Instagram posts given what you’ve read and experienced about Web Archives during this lesson. What are some essential elements that you would consider as you begin to craft this policy?

In their responses, students cited interesting ethical issues surrounding Instagram posts, privacy concerns of those featured in posts, infrastructural considerations with respect to crawl frequency and storage, among other topics.

Reflection

We learned a lot from this experience. For starters, guest lecturing on the week after reading week presents challenges with sustaining student involvement, particularly if the content is asynchronous and not associated with a gradebook item (such as a participation mark). More importantly, we developed this content fully aware that the Google Colab activity would engender some anxiety among students, specifically those not familiar with running or writing code. While we did not ask students to write new code, the appearance of unfamiliar syntax alone was enough to dissuade participation. Based on participation in the activity and classroom discussion, it looks like the Colab portion was a step too far for some students; however, several students successfully completed the notebook and reflected on the experience.

It is one thing to discuss change over time in the abstract and show three examples of change over time (as in the first activity), but quite another to analyze thousands of web pages and demonstrate change over time in a graphical form. What is clear is that we have not figured out how to bridge this technical gap quite yet. The issue may revolve around how content is presented. Nevertheless, a Colab environment is a promising proposition.